Here's my latest "Capitol Games" column at www.thenation.com....

Last week, The Nation and The National Interest held a public discussion to explore whether these days foreign policy realists of the right could make common cause with foreign policy idealists of the left. (The event was titled, "Beyond Neocons and Neolibs: Can Realism Bridge Left and Right" and can be viewed here.) After all, both groups share an opposition to the messianic crusaderism and bullying interventionism of the neocons that has yielded the Iraq war. Speaking for the left were Kai Bird, co-author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer, and Sherle Schwenninger, a senior fellow of the World Policy Institute and a regular contributor to The Nation. The hardheaded crowd was represented by Dov Zakheim, an undersecretary of defense from 2001 to 2004 and now a vice president of Booz Allen Hamilton (who supported the invasion of Iraq), and Dmitri Simes, a former Nixon adviser and now publisher of The National Interest

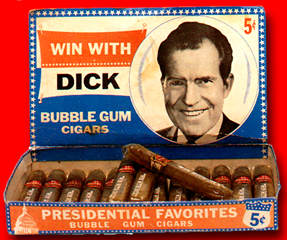

The presentation showed there was not a lot of territory to share. In his opening remarks, Bird noted that Henry Kissinger had been wrong about everything, and he referred to Vietnam and the US support of the military junta that in 1973 overthrew Salvador Allende, a democratically elected socialist, in Chile. Invoking Kissinger as the embodiment of all that has been wrong with U.S. foreign policy for decades was a deep insult to the conservative realists. Kissinger is the honorary chairman of The National Interest. Bird's salvo prompted Zakheim to defend Kissinger, particularly on Chile. (Nixon and Kissinger, via the CIA, had backed efforts to topple Allende.) "Chile," Zakheim said, "doesn't look to me like a failure....Quite a success. It wasn't doing that well in the 1970s." Simes then chimed in: "I'm not appalled by what Kissinger and Nixon have done in Chile. I'm not aware of them ever endorsing torture."

There's realism; then there's callousness. More than 3,000 Chileans were killed by the junta that was encouraged and then supported by Nixon and Kissinger; millions of Chileans lost all their political rights for years, as well. That's hardly "quite a success." And Simes is wrong to suggest that Kissinger was unaware of the abuses of the Chilean regime. The coup occurred on September 11, 1973. A quick search at the website of the National Security Archive, a nonprofit outfit, produced a November 16, 1973 cable from Jack Kubisch, the assistant secretary of state for Latin America, to Secretary of State Kissinger that noted that the Chilean junta had carried out "summary, on-the-spot executions." The cable also reported that military and police units had engaged in the "rather frequent use of random violence" in the post-coup days.

Weeks earlier, at an October 1 meeting Kubisch told Kissinger about a Newsweek story that maintained that over 2700 Chileans had been killed by the junta and added that the government had only acknowledged 284 deaths. Kissinger noted that the Nixon administration did not "want to get into the position of explaining horror....[W]e should not knock down stories that later prove to be true, nor should we be in the position of defending what they're doing in Santiago. But I think we should understand our policy--that however unpleasant they act, the government is better for us than Allende was."

Here were some early indications for Kissinger of the brutality of the Chilean junta. He obviously cared little about what was happening to Chileans apprehended by the junta. And he tacitly went along with the regime's violent means. Two years later, he showed his scorn for human rights concerns when he met with the Chilean foreign minister. At the start of that meeting, according to a State Department memo, Kissinger pooh-poohed the human rights issue. He told the Chilean, "Well, I read the briefing papers for this meeting and it was nothing but human rights. The State Department is made up of people who have a vocation for the ministry. Because there were not enough churches for them, they went into the Department of State." Kissinger added that it was a "total injustice" to fixate on Chile's human rights record.

In August 1976, according to another State Department document, Kissinger was briefed on Operation Condor, a secret project concocted by the Chilean junta and other military dictatorships in South America to conduct "murder operations" against opponents of those regimes. By the way, two months later, Kissinger met with the foreign minister of the military regime of Argentina, which at that time was conducting a dirty war that would come to "disappear" at least 10,000 people (and maybe over 30,000), and Kissinger took a rather casual attitude toward the abuses in that country. As a State Department memo recounted, Kissinger told the Argentine,

Look, our basic attitude is that we would like you to succeed. I have an old-fashioned view that friends ought to be supported. What is not understood in the United States is that you have a civil war. We read about human rights problems but not the context. The quicker you succeed the better‚ The human rights problem is growing one. Your Ambassador can apprise you. We want a stable situation. We won't cause you unnecessary difficulties. If you can finish before Congress gets back, the better. Whatever freedoms you could restore would help."

In other words, get your abuses over with quickly, while I look away. Unfortunately, the fascistic and anti-Semitic Argentine military regime would continue to disappear and torture its citizens for another seven years.

I'm all for reaching across the ideological divide, seeking common ground, making alliances. And Simes--unlike Zakheim--advocated working together whenever possible. Referring to the current course in US foreign policy, he noted, "This republic is facing a mortal damage," and the Bush administration is "pursuing policies that make us more vulnerable."

But foreign policy intellectuals should not forget about the past as they move ahead. I appreciate the fact that realists fancy being hardheaded. Simes noted that he was aghast at the corruption and state violence he saw when he recently visited Russia. But he added that since the United States needs Russian assistance in dealing with Iran and North Korea a realistic approach has prevented him from insisting that Washington pressure Moscow too forcefully on issues of corruption and political rights.

Such calculations--whether correct or not in the particulars--are understandable. They have a logic to them (whether you agree or not with that logic). But, please, let's be realistic about past decisions and calculations. It's not realism to sugarcoat history and to deny responsibility for actions taken. Those who distort the past cannot be expected to save American foreign policy from those who distort the present.

CORN VS. GREENBERG RE WOODWARD. Day 4. He gets the last word in out face-off on The New Republic site. You can see it here. I'll read it, too. Afterward, I'll post some final thoughts on this site.

CORN AND ISIKOFF ON C-SPAN. We'll be on C-SPAN's Book TV discussing Hubris: The Inside Story of Spin, Scandal, and the Selling of the Iraq War, on October 21 at 8:00 pm, Eastern time.

Posted by David Corn at October 20, 2006 10:44 AM